Fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda, was reported for the first time in Africa in early 2016 in Nigeria, Togo, Benin, and São Tomé and Príncipe. While Africa has a native species of armyworm, Spodoptera exempta, which eats mainly the leaves of maize plants, the effects of fall armyworm are more devastating because it eats not only the vegetative parts of the plants but also the reproductive parts by eating the cob itself. This is more destructive species, quickly ravaging much of the continent, is actually native to North and South America, but how it was introduced into Africa is still unknown.

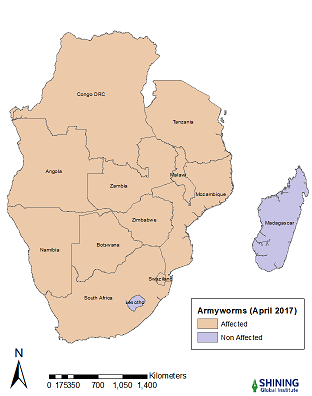

In January 2017, the fall armyworm outbreaks were reported in several countries of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) region—Zimbabwe, Zambia, Malawi, and Namibia—and by April 2017, most of SADC countries were affected. Though Lesotho and the island nations (such as Madagascar and Mauritius) have not yet been affected, these countries remain at high risk. Figure 1 shows the rapid expansion of the pest infestation in the region.

Figure 1. Countries affected as of April 2017

What are the economic impacts for the SADC region?

CABI (2017) estimates the cost of losses so far at $13.38 billion for maize, sorghum, rice, and sugarcane in all confirmed and suspected fall armyworm presence in African countries. For maize—the main crop and staple food of most countries in the SADC region—production alone, the cost of losses is estimated at $3.06 billion. Given the importance of this crop, the damage to its production certainly threatens food security, though a thorough assessment is still needed to evaluate the severity of the impact.

Responding to the outbreaks

Given the rapid spread of the outbreaks, local and national responses are not sufficient; it requires a regional, and even a continental, response because other African countries outside of the region, including Nigeria, Ghana, Kenya, Ethiopia, Uganda, Benin, Rwanda, are also affected. African leaders have to recognize that a lack of treatment or determination of one country to combat the pest could undermine the efforts of other countries due to the moth’s capability to fly distances up to 1,600 kilometers. At the national level, the capacity of each nation to respond to the pest infestation depends mainly on the availability of resources. So far, the emergency measures taken by many countries have been to distribute and spray pesticides in the affected areas to contain the spread of the armyworm. But there needs to be sufficient information and clear recommended actions for farmers so that they can immediately reduce production losses. Related to these challenges are financial constraints.

How much of the agricultural budget should be spent to fight the armyworms and contain the outbreaks? The ministries of agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa, despite their governments’ continent-wide commitment to allocate 10 percent of national budget to the agriculture sector, are usually under-funded, which constitutes a main challenge. It’s time for national governments to deliver on their long overdue commitment to the agriculture sector. Without action, the call for and largely admitted strategy to boost the African economy by increasing the investment in the agriculture sector remains unanswered or only partially answered. The armyworm infestation puts even more, urgent pressure on these thin budgets. But the situation is incredibly complex: Combatting the fall armyworms cannot cause other factors related to the agricultural development, such as human, technical, and institutional issues, to be overlooked.

At the regional level, FAO, SADC, and the International Red Locust Control Organization for Central and Southern Africa have triggered a regional response by organizing an emergency meeting in Harare, Zimbabwe in February 2017, to coordinate responses (FAO, February 2017; SACAU, March 2017). Several recommendations were taken, including the urgent need for strengthening information and surveillance systems through sharing of information at national and regional levels, the improvement of early warning systems, and the need for research to fill information and knowledge gaps. In April 2017, FAO Regional Office for Africa convened a technical meeting in Nairobi, Kenya, where experts “have called for robust monitoring of the pest in order to respond effectively.” Regional cooperation is crucial, not only in term of coordinating and monitoring responses but also in raising financial resources and defining the level of working relationship by sharing available technical expertise and other resources between participating countries. These international responses and their success, however, still require a strong national commitment and resources; the implementation of the policy and technical recommendations depends on local governments and other national stakeholders.

The emergency measures that have been taken at the national and regional level should be coupled with a thorough assessment to determine the areas affected, the severity of damages and their consequences on maize production and other crops, and the effects on food supply. For the medium and long term, further research will determine how the pest spreads and explore the best methods to combat or control the fall armyworm. Strategy and policies are efficient if they are based on scientific data.

Marius Ratolojanahary

* This article was first published in Brookings Institution's blog, Africa in Focus, on June 7, 2017