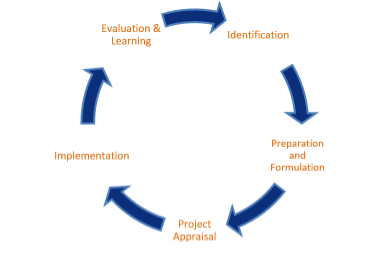

Project cycle

During the project design process, the project designer lays out ideas, which serve as the mainframe for a project proposal. For development professionals who are working in the agricultural development sector, the project ideas can be an introduction of a new technique in agronomy, a new agricultural input, or an extension service method, etc. Sometimes, these ideas are not new at all, but are successful agricultural development models from one location or country that a project designer wants to implement in another location. When an idea has been approved to receive funding, developers conduct a test on a limited scale—a pilot project. Obviously, the result of the pilot project implementation is either a success or a failure. On the one hand, if the pilot project fails to achieve its objectives, the project designer either abandons the model or continues to analyze the origins of failure and improves the design for future testing. On the other hand, if the pilot project succeeds and meets its goals, the project designer wants to implement the project on a larger scale. The debate begins here because sometimes a project fails when implemented on a larger scale. Why is that? Why does a pilot project succeed, but the following implementations fail?

I experienced and witnessed this dilemma during my career in the agricultural sector. Based on my years of experience, this paper is my reflection on the possible explanation of failure of small scale farming in the developing country. I do not pretend to provide a comprehensive explanation, but it is rather the major factors that I encountered.

Why does scale-up definition matter?

Let’s begin with the definition, the Merriam-Webster dictionary defines “scale-up” as an increase according to a fixed ratio. The definition implies that there is a defined amount or size at that outset so that any increase can be calculated. For example, assume that a company has 10 trained employees out of a workforce of 100. The employer wants to increase the number of trained employees from 10 to 60, to that the ratio moves from 10/100 to 60/100 trained employees. In other words, we know the identity of the potential training beneficiaries, which is the 100 employees in the example. The employer scales up the training program to reach 60 employees out of 100. The example seems to be straightforward. However, in the agricultural development project, it is more complicated.

In an agricultural development project, it is not always clear if the scale of the project refers to the size of the farmland, the geographic distribution of the project, the number of livestock, or the number of farmer beneficiaries. The controversy between the government and donors is the result of the misunderstanding of the word scale-up. The government often wants the implementation of the project to reach different regions in the country, which is the geographic distribution. The donors might think about the number of beneficiaries, regardless of the geographic distribution. These are two different project indicators, and neither necessarily includes the desires of the beneficiary farmers.

An agricultural development project has, in general, a specific project. That means mission, objectives, and beneficiaries are clearly stated with respect to product and geography. If the project is about improving the rice production, the beneficiaries (i.e. the target population) are rice farmers, not maize farmers or wheat farmers. The goals also should be clearly defined, for example improve yield per hectare from X kg to Y kg. These two statements imply that the project is implemented in specific geographic areas for rice production and targeted specific rice farmers, who have the abilities to improve their rice production, not all rice farmers.

The geographic location defines the potential agro-ecological areas better for rice production. Several factors come into play in this case. First, climate-specific location: the weather and climate are the main conditions, particularly in the rain-fed agriculture. However, depending on the country and the region, the project’s success depends on other factors as well, such as the need of irrigation infrastructure, soil nutrients, etc. Therefore, the implementation areas for the pilot project itself must be chosen among specific conditions. It is generally likely that implementation of the pilot project in those specific locations will succeed in reaching the objectives. “Likely” is the right word because there are other factors for success. In other words, scaling up a project does not mean it can be implemented in all areas of the country or in all rice production areas of the country.

Rice field

Expanding a project on a larger scale will succeed in the areas having similar environmental conditions as the pilot project. In practice, this assumption implies two options: first, the location of the pilot project itself should be well-defined during the project design. That requires a knowledge of the country or region and the future expansion of the project. The pilot project should be implemented inside of these areas having the same environmental conditions. Therefore, scaling the project up is literally the geographic expansion of the pilot project. Second, the exact environmental conditions do not exist, but there is a slight difference between two or more areas. In this case, the project designer should predict some adjustments during the expansion and design a flexible approach. The example of the rice production earlier, the project is expected to be expanded in one geographical area having the same amount of rainfall, but the temperature needed for the rice production in the second area is expected to last during a shorter period only (e.g. microclimate). In this case, the project must predict to find suppliers of short cycle rice seed varieties, which are not the same variety as the seeds used during the pilot project. The idea is to implement the pilot project in the area where the environmental conditions are the closest to the expected expansion areas.

Target the commercially oriented subsistence farmers

The project targets a specific category of farmers, and this category must be carefully defined. The majority of small scale farmers are subsistence farmers. However, not all subsistence farmers are the same. The first category of subsistence farmers includes those who can or wish to be commercial farmers if the business environment improves and if they have access to the agricultural inputs, services and market. The second category of farmers includes those who stay as subsistence farmers or seek to be employed to other farmers. Sometimes, this latter may have other sources of revenue, but they still have a farm to fulfill the needs of their family. Regardless of the business environment, technical training, or access to agricultural inputs and services, their status will not change much. Both may be farming rice, for example, but they are farming for different reasons. Therefore, the real target to scaling-up a project is the first category of commercially oriented subsistence farmers. With the help of the project those farmers can really make the difference.

But how do you identify these two categories of subsistence farmers for scaling purposes?

In a country where 70% to 80% of the population live in rural areas, it can be challenging to identify which farmers belong to each category of subsistence farmers. There is no clear dividing line for the two categories. The identification step is crucial to the success of bringing the project to scale. The pre-design phase, or data gathering phase, plays an important role in the identification. This phase should include field visits and surveys. The project designer team can gather important data about the targeted beneficiaries, but only if they recognize the different farming motivations. The team should already have an idea about the characteristics of the targeted small farmers: technical knowledge and skills, ability to adopt new techniques, behavioral attitude towards change, social and economic engagement, etc. You may not have exact figures; however, you have an approximate proportion of the targeted population. Taking into account and keeping these characteristics in mind during the project design process will have an important impact on the implementation and the results of the project. That means, the failure of scaling up the project might be the result of the lack of field knowledge and information, or simply skipping this phase. This could result in trying to scale up farmers that simply have no desire to scale up.

Include the future project executive among the development team

The second step is the implementation of the pilot phase. This phase will help to confirm the data gathered during the pre-design phase and will deepen the knowledge of the implementer teams about the beneficiaries. One issue arises often during the pilot project implementation; the implementing manager did not participate with the development team during the project design. This situation can impede the overall understanding of the project concept and context. As aforementioned, the design phase includes the identification of project beneficiaries. Among these beneficiaries include those who are not the ultimate target of the project. These identification processes cannot be transferred entirely to a new implementing manager because the environmental and personal relationship context that the developer experienced during the design phase cannot be easily explained and understood for the new implementer. I define the circumstances as the design-implementation gap. The context design-implementation gap may not undermine the pilot project, but can be hindered the result of the expansion phase. The explanation is on a small scale, the small number of beneficiaries is well-managed and under close supervision. Any risk of negative results is rapidly adjusted. Therefore, the project meets the expected goals. However, at a larger scale, the consequences can be huge because the size of the beneficiaries increases, which means the management cannot be exactly the same as during the pilot phase. The micro-management style does not work at this scale. Often, the issue is considered as a lack of project ownership. Thus, including the future project executive among the development team addresses the issue.

In addition to the project appraisal, the implementation team has to pay attention to the ability and willingness of the beneficiaries to adopt the project. You need to have a clear picture of the category of farmers who are willing to move to the next level, which can be determined through different signals and behavior during the project implementation. For instance, during technical training series, you may have several farmers who are very enthusiastic and have a good attendance, but when you do the farm visits, they do not adopt or even try to apply the techniques being learned. Their behavior tells you they are not the farmers that you want to target, at least at the initial phase. If you spend too much of the resources toward these farmers, failure is predictable. Depending on the results of the pilot phase, some adjustments are necessary if not crucial to the success of the entire project. I want to point out that some farmers usually are waiting for the success of their fellow farmers before changing their routines, adopting new techniques or new seed varieties. This farmers’ behavior emphasizes, again, the crucial period of beneficiaries’ identification phase.

Lastly, failure of scaling up is not solely due to poor target beneficiary identification. There are other internal and external factors to the project, which interact to determine the result of the project implementation. The external factors include transportation, access to markets, access to agricultural inputs and agriculture services, political pressure or instability, etc. While these factors play their specific role in the project success; often, the projects fail to scale because the beneficiaries are not sufficiently understood and defined. The projects underestimate the real target population in favor of the other project components.

Marius Ratolojanahary